No. 5 | Urban Sense: Stability in context, setting

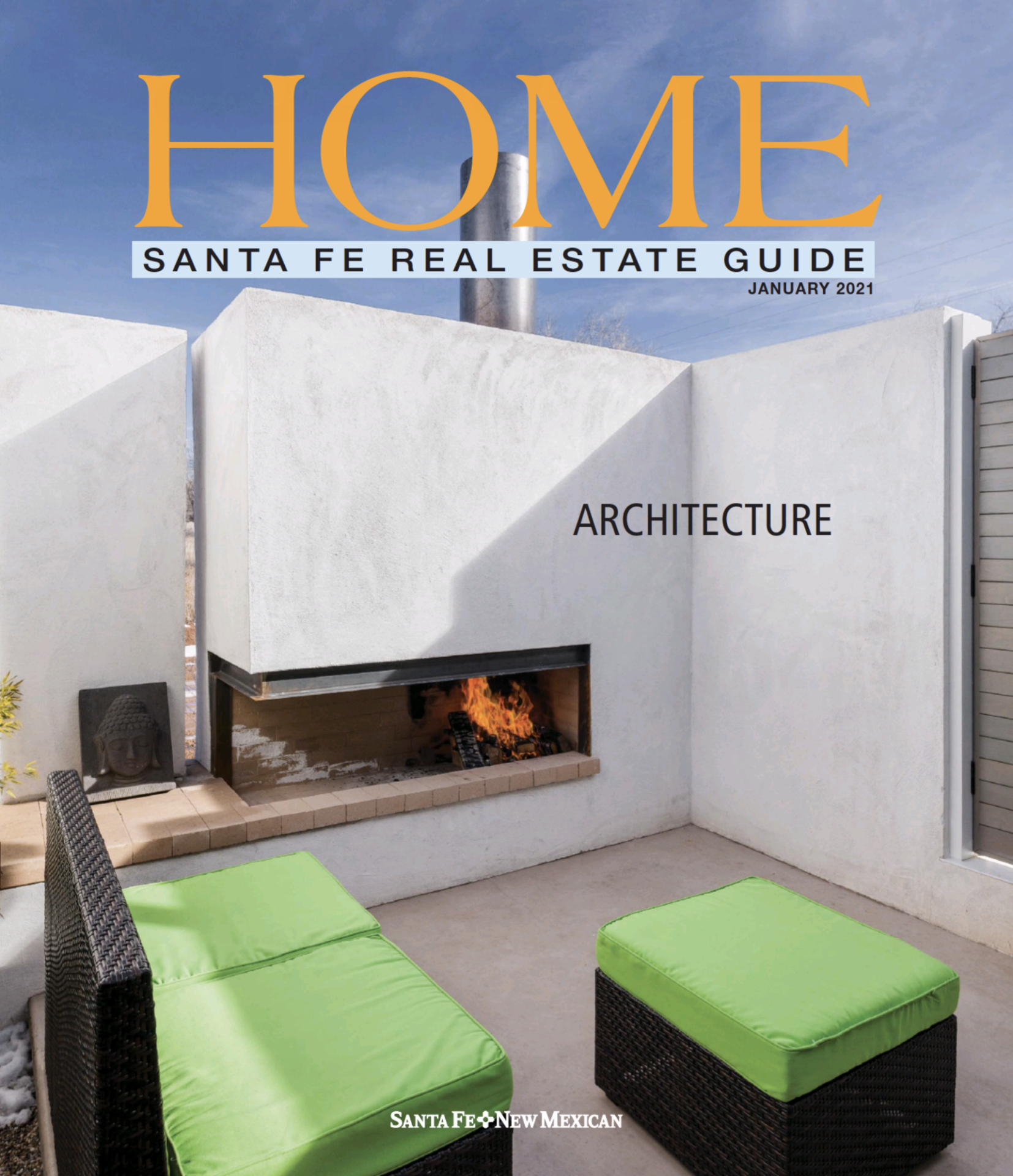

In the January edition of The Santa Fe New Mexican’s Home Magazine, I talk about change and how it impacts the world around us. Urban Sense.

Read The Article:

I have been driving the same road for 30 years, over the same path the conquistadors used, the Indian traders used, the Kiowa and Comanche people used to trade with and war with each other. I have watched the landscape through the windshield, looking for antelope and hawks, and now abandoned buildings, roads and fences from the farm/homesteads falling down and disappearing back to form, back to their original settings.

In Santa Fe we go to great lengths to save falling-down buildings in our little adobe enclave, even penalizing those that abandon the maintenance of their mud hut, because we see these buildings as representing our culture, our heritage, and now our tourism dollars. Are the buildings out in the “middle of nowhere” less important, less valuable, less meaningful? These buildings were often built in the same time frame, with the same materials. So what about them makes them less important? Should we apply the same logic to both and allow them all to disappear into the earth, as I have seen in Hopi?

We in Santa Fe decided over 100 years ago to stop the modernizing and Americanizing influences on our buildings, going so far as to remove those elements that didn’t follow the Spanish or Pueblo style. Although we have moved a few roads, added a few roads, and straightened out a few intersections over the years, we have gentrification, not abandonment. We actively manage change; we do not allow nature to take its course. We save things based on age, association with famous people or events, character and uniqueness, according to federal, state, and local laws as written by the United States Secretary of the Interior. We can also justify saving it because of the embodied carbon already expended to make this or that building. Managing change in our mostly urban setting makes economic and environmental sense. And these objects will continue to teach us about ourselves.

People die and places die, too. People move away, and some never come back. It seems especially true where the homesteaders were lured out of the 19th-century European and Eastern cities with promises of 160 acres, which they soon learned in the high desert won’t support very much livestock or a family, especially during a drought. Perhaps these buildings that are falling down represent dashed dreams, or maybe lives well lived, out in the country, far from town. In a place like Santa Fe many families hold on, and have held on, but still things change. We might camouflage the change; sometimes we name buildings after their previous owners, or function, for example the Palace of the Governor and Fort Marcy, to help us remember our past, but other than recently calling for a land acknowledgment for Oga P’oghe, the historic or pre-historic evidence of the Tewa people in Santa Fe has disappeared, or is below ground, below sight, or covered over. Context and setting — perhaps those remain the most important, not the buildings in camouflage, but the river falling out of the mountains, the far off views of the plains and mountains.

Consequence: Life is long if we are lucky. Life is complicated and complex and full of serendipity. Embracing the ephemeral seems appropriate to understand the loss of life and the loss of buildings. Is it unnatural then to preserve buildings that should be allowed to melt into the earth? We preserve to remember our values, our people and our history, the poignancy of life. I will keep driving the road between my adopted home and my native home, between Pueblo and Apache land and Kiowa and Comanche land. I still see the antelope herds visible from the road, the hawks still wait on the fence posts, and I will keep looking for the first glimpse of the mountains after leaving the plains. And I will see the buildings gradually melt into the earth. In this land change is allowed to look like change.

Gayla Bechtol received her architecture degrees from Harvard University Graduate School of Design and from the University of Southern California. Gayla Bechtol Architects is a design-centered architecture/urban design/historic preservation practice that has created designs for homes, institutions, and urban spaces for nearly 30 years. Bechtol practiced deep democracy while leading the citizens of Santa Fe to the award-winning Santa Fe Railyard. She is a board member of Friends of Architecture Santa Fe.

Related Articles

No. 28 | Urban Sense: Dreaming of a Future Optimism

In the July edition of The Santa Fe New Mexican's Home Magazine,...