No. 25 | Urban Sense: The Tectonics of Change

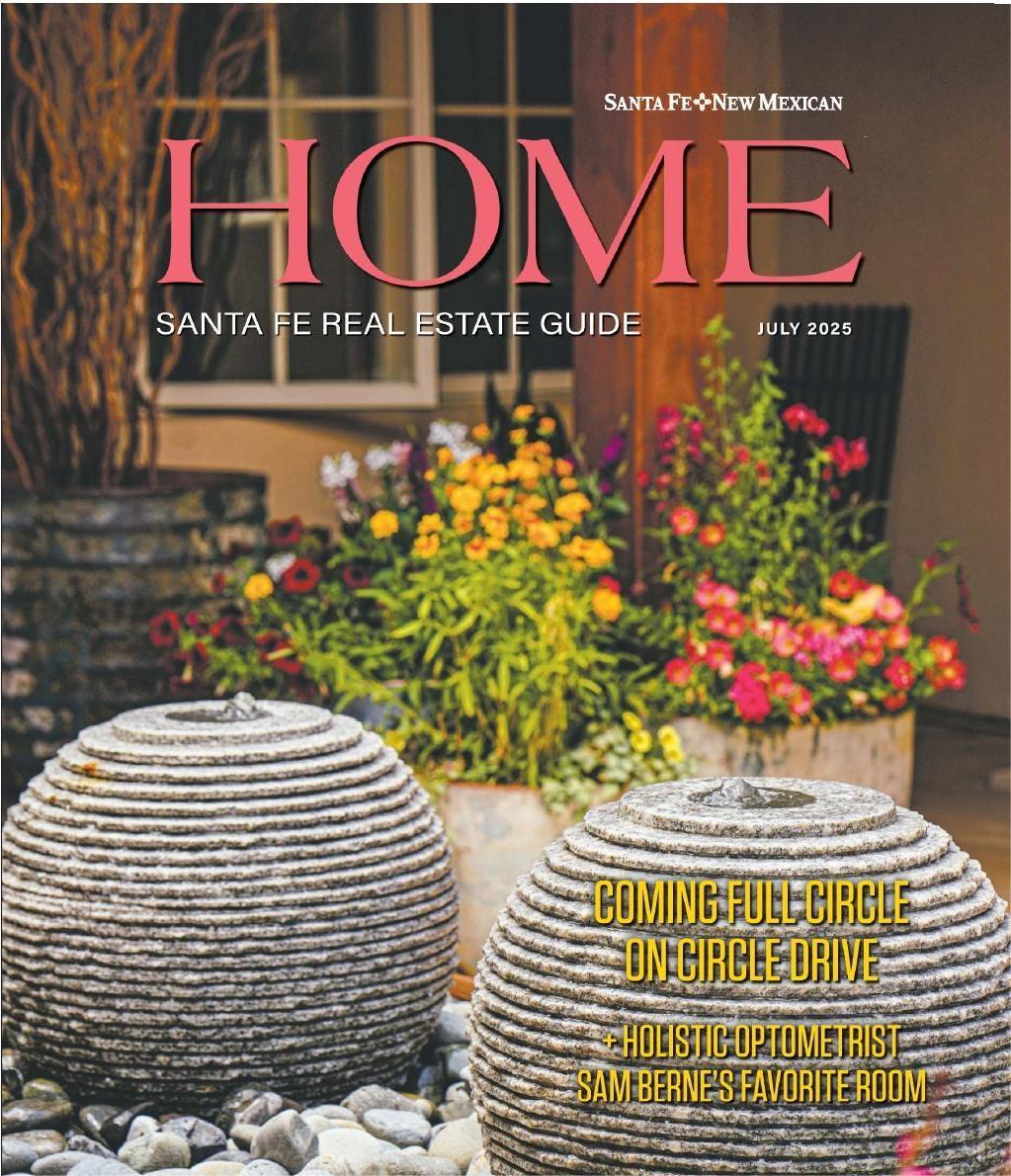

In the July edition of The Santa Fe New Mexican’s Home Magazine, I discuss the architectural evolution in Santa Fe, emphasizing the influence of vernacular and New/Old Santa Fe Style through architects like William Lumpkins and John Gaw Meem, and I advocate for a balance between preserving this heritage and adapting to contemporary needs by promoting more inclusive zoning and housing policies to accommodate a diverse population. Urban Sense.

Read The Article:

When an architect arrives in Santa Fe, they tend to find themselves needing to address not only the vernacular architecture that still exists but also the later overlay of New/Old Santa Fe Style from over 100 years ago (a style itself based on the extant Spanish and Pueblo buildings and churches). Architects, new and old, have the privilege of seeing the construction of Zuni, Taos, Acoma and Chaco in person, and are afforded the opportunity to admire—again, in person—the archeologists, architects and artists who invented the style that seeks to elevate and evoke the vernacular that existed in Santa Fe for centuries. This imposed Style, which exposes the tectonics of building in mud and timber and the fortified land-use patterns, and then sometimes adds in outside elements (like windows from the East Coast), gives the arriving architect something to respond to—other than the blandness of what most buildings in most other suburban developments present. This was true in the early 20th century when John Gaw Meem arrived, when William Lumpkins practiced in the mid-century and it was true when I first arrived to Santa Fe in the 1990s.

Recently, I took another look at Lumpkins (1909-2000), a native New Mexican who’d formally trained elsewhere as an artist and later as an architect. I’m renovating a house that he designed and am looking at not only his Pueblo fantasies but also his solar houses and his La Casa Adobe houses, where for the most part, he designs buildings around courtyards, predominantly done in the Spanish Pueblo Revival style as a response to the rebellion from what he called dead modern architecture that was so ubiquitous all over America at that time. A stylistic “rebellion” that had replaced the “gingerbread” look of most revival styles—like Queen Anne and Greek Revival. In 1961 he wrote a sort of manifesto in which he spoke of the need for a “Regional resistance to uniformity.” He saw that the modern architecture, also known as the International Style (developed in the 1920s and 30s), led to monotonous buildings and lamented that it had become a formula for architects all over the country. This was a challenge for architects to use adobe, not masonry blocks; to employ actual earthen architecture in order to exploit the sculptural quality of adobe, a homemade, site-specific material (which, back then, was a novel if not revolutionary idea).

When John Gaw Meem arrived in Santa Fe in 1920 (for a stay at the Sunmount Sanatorium to alleviate the tuberculosis he’d developed in his native Brazil), he embraced the New Old Santa Fe Style in a different way. He used Beaux Arts planning principles such as axiality in almost all of his buildings, and he looked for the modern material to update this Style. He was a proponent of pentile (a building material of hollow tile bricks that were fabricated at the old state penitentiary) as opposed to the adobe that had been used to make so many of his institutional buildings. The exception is the Cristo Rey Church, made of adobe, but he also used steel in its construction.

Today’s question is: How do we keep our New Old Santa Fe Style but progress beyond the exclusivity it now represents? Should we have looser standards or more choices? Less copying of the elements while still honoring the tectonics of the vernacular architecture?

Tectonics is the way the gravitational forces from the roof find their way to the ground, and so whether they find their way by lintels and bond beams or by massive walls, these forces always have to meet the ground. Here is an architecture that exposes how to mediate gravity. We are still responding to that idea in architecture and preservation. Santa Fe style has allowed for a different way of living and being in the world, but it is more exclusive than ever.

Practicing architecture in Santa Fe is interesting and rewarding. I love the public debate about style and preservation but now more importantly there’s more talk about its relevance. To whom is it (most) relevant? Whose history is it? Santa Fe has a particular take on preservation and style because we had a style ordinance for sixty-plus years—something we now call “preservation.” This “preservation” maintains a style and has preserved numerous buildings of this “preserved” type that is now more than 50 years old; some of these buildings have character-defining features as recommended by the U.S. Department of Interior Secretary’s Standards, but some are, well, let’s admit it, just plain old. Yes, we want the Style and Preservation to be relevant to everyone but I feel that the arguments for Style and Preservation miss the point if the style and preservations are irrelevant, if the people who work in Santa Fe are unable to live in Santa Fe—because of our adherence to style and preservation. (Again: for whom are we preserving these styles?) Preservation can also be seen as an exclusionary zoning tactic, just as large-lot zoning can be seen as an exclusionary zoning tactic that keeps out those who can’t afford a larger home.

Speaking of large-lot zoning: The densest part of Santa Fe is densely built, but it’s not necessarily densely populated. We are surrounded by National Forest but insist on keeping large-lot zoning left over from the 70s development of the hills around downtown Santa Fe. We need to find our way to building more houses along those streets. If more people, especially working people, can live closer to their jobs we can reduce our collective carbon footprint by reducing traffic as a city.

In the 90s one could still see Old Santa Fe Trail wagon ruts; today, these are mostly hidden behind walls. This makes me question: Have we lost our way with preserving the things that we might care for now? And what we will care for later? If we don’t preserve a place for (most of) the (other) people to live in it as well, we are definitely going to miss them. And then all we have are monuments (meaningless ultimately), or we’ll have meaning for a few and only the tourists will care to see it.

The City of Santa Fe’s General Plan Update is coming up. Stay informed so we have a community that is not just streets and so-called traffic, it’s not just the parks, it’s about housing, it’s density that allows for vibrancy. In this planning process, what is the most important to us will be revealed and hopefully acted upon. The question, though, remains: How can we preserve what we have, Style or otherwise, while also allowing for a cultural change and for more people to live in our town?

Friends of Architecture Santa Fe will soon have bike and walking tours to explore what is preservation and what is style and what’s happened in the City Of Santa Fe in the last 120 years. Please join us. www.architecture-santafe.org

PS: Please build the bridge over Arroyo Chamiso to open up more housing in Tierra Contenta and allow more density in all areas. Our community depends upon it.

Related Articles

No. 28 | Urban Sense: Dreaming of a Future Optimism

In the July edition of The Santa Fe New Mexican's Home Magazine,...