In the September edition of The Santa Fe New Mexican’s Home Magazine, I discuss the challenges and importance of preserving historical and cultural heritage in Santa Fe, balancing modern development with the need to maintain authenticity and honor the past, while highlighting the role of various institutions in ensuring a living preservation. Urban Sense.

Read the Article:

When the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Heritage law, also known as the Monuments Act of 1961, went into effect over 60 years ago, it designated not only houses, churches, farms, mills, town halls and castles as worthy of preservation, but also, if more than 50 years old, village views, areas of old buildings, canals and associated greenery. What a concept.

No matter where we live, but especially in Santa Fe, we often ask ourselves how to deal with the past while planning for the future: What do we preserve, how much and in what ways. For future generations we acknowledge the need for the social/economic life of its historic centers; if the future is to have any sense of itself, a sense of place for its future citizens, these older centers need to survive. They need to be protected and preserved. We search for authenticity, trying to balance our desire for preservation—that the place we want to preserve stays as close to its roots as possible—while doing our best to accept the reality that all things change. The hope, the goal always being: keep that place as close to what it actually was when we first dis-covered it, or to how it was while we were children (without being overly wedded to something that’s more nostalgia—and not preservation).

We want to integrate both social and physical preservation, and encourage economic growth and employment development, while at the same time preserve the quality and meaning of our physical heritage sites. These competing desires set up a power struggle among different populations—professionals, decision makers, entrepreneurs, outside investors. And as we have witnessed in Santa Fe many times, sometimes determining the outcome of a land-use case has come down to some-thing as seemingly arbitrary as the number of people who showed up in council chambers at the time of the vote.

Downtown Santa Fe is similar to other city centers, these centers often being the most valued environments, and so, just as often, when it comes to what to do with these historic areas, they often become scenes of intense conflict. We keep the physical heritage but ditch the existing populations. The conservation movement is concerned with the spirit, not only of urban conservation but also natural conservation. We concentrate our attention on one area of Santa Fe, at the expense of the other parts of Santa Fe, oftentimes increasing the cultural onslaught of suburban/vehicle-oriented development in the south and west portions of the city, while only paying lip service to people wanting equally appealing walkable communities in areas other than downtown.

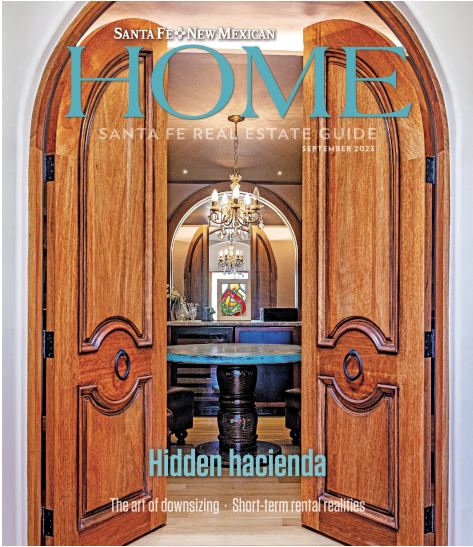

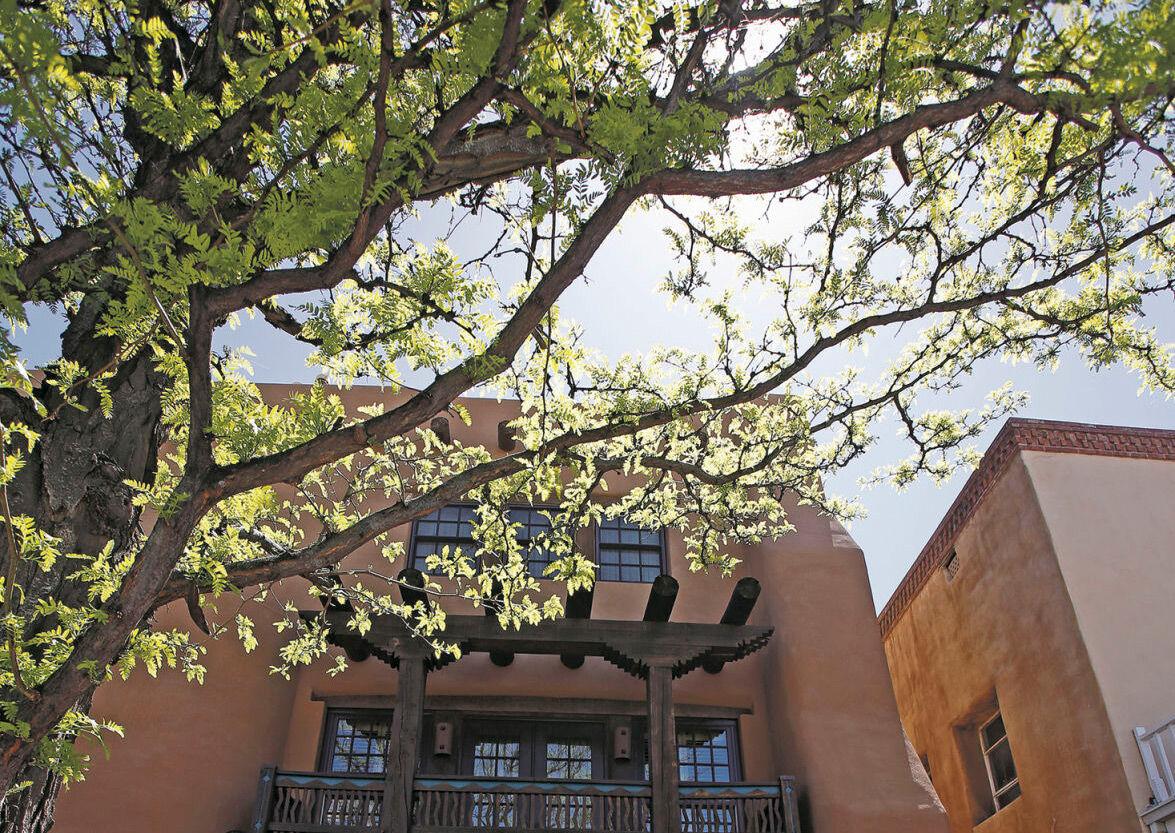

Downtown Santa Fe is a beautiful and pleasurable architectural and urbanist experience that always inspires—and serves as a reminder that insensitivity to context is not the only alternative. The homogenizing impacts of global capital are one of the greatest threats to our positive differences and artistic invention. Our role as an artistic place is an ever more crucial hedge against the planetary sameness and planetary peril.

Santa Feans are now facing the loss of the last grocery store on the Eastside. And old houses continue to be converted into anything but new or updated housing all over the downtown area. Many of these houses-cum-businesses exploit their downtown (i.e., inherently “historic”) con-text, some incorporating this heritage in as honoring and honorable a way as possible; they make it not just a selling point but bake into who they are, it becomes part of their educational mission, something they see as a responsibility to the past. A past in which they do their other work. These include the Old Santa Fe Association, the School for Advanced Research and the Historic Santa Fe Foundation, and for the last ten years the Women’s International Study Center. All of these institutions are in buildings originally designed for families to live in. They survive today as something else, mostly to preserve a moment in time, through their physical heritage, allowing the past to become relevant for the future. Allowing for new uses allows for a living preservation, preserving a balance but allowing for change, for a new interpretation of the past. We can say yes to more development. But we also need more information that honors the old families, the original land stewards, the indigenous—the who and the what that came before—publicly.

Instead of finding ways to say no to the new, to the connections to the past and future, let’s highlight our shared values, let’s find ways that highlight our common cultural heritage.

Let’s remember we don’t own the earth, let’s listen to one another to make better decisions.